Influence of cooking classes on healthy and sustainable food choices by Nigerian women

Nigeria is the most populous nation in Africa and half of the population live in the urban areas.

The country is provided with a wide range of agricultural food products, such as cocoa, various grains, nuts and seeds, tubers, cattle and fish. Yet, millions of Nigerians face hunger and malnutrition while living in the face of abundance. Malnutrition appears wherever there is a deficiency in nutrients.

The current education program was meant to empower college educated women to make nutrient dense meals for their families using little resources. Furthermore, it was designed to study the effect of cooking demonstrations on behavioural change. Fifteen participants, women between 27 to 59 years old with college degrees, took part in four cooking classes.

The nutrition education program helped to boost the women’s creativity and empowered them to prepare nutrient dense meals from whole, seasonal and local foods at lower cost.

Gaining understanding of the significance of nutrition for health and developing skills to prepare healthy meals may be the initial steps towards a healthier lifestyle.

Introduction

Adequate nutrition is an essential component of health and is crucial for a good quality of life. Though Nigeria is well provided with a wide range of agricultural food products, such as cocoa, peanuts, cotton, palm oil, corn, rice, sorghum, millet, cassava, yams, cattle, sheep, goats, pigs, fish and many others1, the National Policy on Food and Nutrition in Nigeria (NPC)2 observed that a large number of Nigerians do not have the means to access adequate amounts of food to meet their basic needs for optimum functioning. The national food production declined while the population has been growing in spite of efforts by the government to stimulate food and agricultural production using various incentives. As a result, in Nigeria, as in other parts of the world, malnutrition (the pathological condition brought about by insufficient nutrients that are essential for survival, growth, reproduction and capacity to learn and function in society3) is becoming the biggest public health problem. Yet, so far it has not been well confronted nor is it even being considered a main problem by decision-makers4.

Malnourishment is a serious health problem that transcends all ages in the society. According to Odum5 undernourishment is the cause of certain diseases sweeping across parts of the world, especially Africa, in which an estimated 240 million people are affected. Unbalanced nutrition affects children more than adults. In Nigeria, half of all under five deaths are due to malnutrition6. The National Demographic and Health Survey (NDHS) of 2013 indicates that 37% of children under five are stunted or too short for their age7. Parents greatly influence children’s food consumption, choices and preferences by acting as role models8. Lack of access to information and pervasive ignorance of the health impact of nourishment has been identified as the major factor militating against proper nutrition for children in Nigeria9. As such, education about nutrition is regarded as an important component in promoting healthy eating habits10; 11 and boosting confidence in cooking abilities especially if the nutritional content of foods is understood. Hence, the first step to solving the national problem of malnourishment would be to identify simple and efficient methods for improving knowledge of nutrition and fostering creative efficiency in preparing healthy meals.

Personal Interest. My interest lies in the fact that the significance of nutrition receives insufficient attention in Nigeria. In spite of the gradual rise in cases of cancer, diabetes and kidney failures, the policy makers are still poorly informed about the importance of education about nutrition. Nutritional educative programs are often discussed in relation to agriculture, never on their own merits. Moreover, the national strategies in Nigeria tend to prioritize food fortification and supplementation as direct nutrition interventions12.

The lack of knowledge and creative skills in meal preparation highlight the need to provide nutrition education programs and cooking demonstrations. The current education project was developed to determine the effectiveness of cooking demonstrations in order to enable college educated Nigerian women to make healthier food selections with limited resources in order to mitigate and/or prevent health problems that may result from malnutrition. More precisely, I examined whether participation in cooking demonstration and informative classes

a) increases participant’s ability to identify and select nutrient dense, whole, seasonal and local foods,

b) increases participant’s confidence in creatively preparing healthy meals using limited resources and

c) contributes to behavioral change.

I hypothesized that cooking demonstration and nutrition education will help people to understand the causes of malnutrition, enable them to make healthy food choices with limited resources and creatively prepare healthy meals to prevent malnutrition.

Project implementation

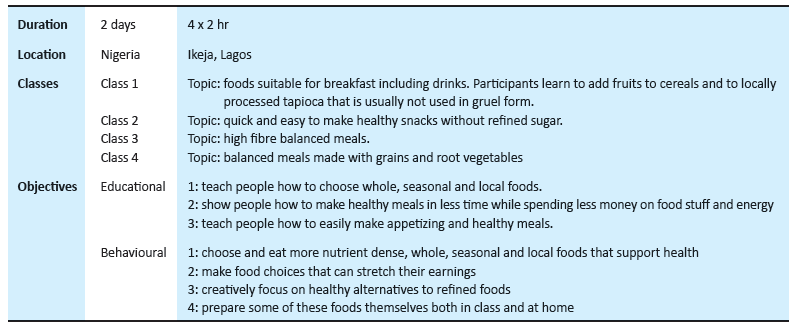

An overview of the project can be found in table 1, including its objectives and topics.

Materials and Participants. The project was carried out in Ikeja, Lagos, Nigeria. The kitchen used (about 18.5 square meters in size) was especially built for cooking classes. Two weeks prior to the program, participants were invited to the program via phone calls, text messages and emails. Ninety (90) invitations were sent out, forty-five (45) women accepted to take part in the program and only fifteen 15 turned up. The reason for such low attendance was probably the participants’ anticipation of a terrible traffic situation around the program venue. All fifteen people who participated were employed (100%), above 25 years of age (100%) and college educated (100%). Of the fifteen participants, twelve were married (80%) and had at least one child (80%) and three were single with no child (20%). Participants were assessed as being able to strike a balance between the affluent and the not so rich with regards to their purchasing power.

Health and Knowledge Examination. Eating habits, knowledge about healthy foods and limitations in choosing healthy food products were assessed through pre-test and post-test surveys. In the pre-test, 11 survey items focused on participants’ knowledge of healthy foods and their limitations. Two questions addressed participants’ assessment of themselves and what they think they know about healthy foods. The same questions were repeated in the post-test with an additional 5 questions on the usefulness of the program.

Food Products. The food products used in the project can be found in Table 2.

Cooking Demonstration. Cooking demonstrations covered basic cooking skills, 15 local sustainable foods, recipe conversion, label reading, food measures and food servings.

Nutrition Education Pieces. Two educational booklets were used to enable participants to make healthier food selections: a 5-page brochure about preparing and tasting foods and a 25-page booklet providing information on nutrition.

Prior to the program, several discussions took place to identify the thoughts and concerns of the participating women as well as their suggestions which were then integrated into the program. On the day of the program, prior to the start, I offered a formal introduction and presented the participants with a folder containing the pre-test and post-test form, brochure and booklet. The information was collected anonymously.

Discussion and conclusions

Nigerians have been enticed with refined foods depicted by the media as ‘foods for the privileged’ without the commensurate advertising of the diseases associated with such nutrient depleted foods. Through cooking and tasting classes, selected college-educated women were taught ways to make and eat whole, seasonal and local foods to stay healthy. The project was planned in such a way as to increase nutritional knowledge and creativity in the participants.

The pre-intervention survey confirmed that a lack of knowledge was a big hindrance in healthy feeding. Initially, most people did not know what whole foods were. However, the post-intervention survey proved that cooking demonstrations and nutrition education increased participants’ knowledge and enabled them to identify and choose nutrient dense, whole, seasonal and local foods that support health.

In some cases, time and money were found to be major limiting factors in feeding a family with healthy foods. For instance, after the intervention the participants still could not bring themselves to choose butter instead of margarine. They chose rather to abstain from buying. The reason given was that margarine is less expensive than butter. That is understandable, since butter is not manufactured and packaged in Nigeria. All the butter in Nigeria is imported. Overall, the project outcome proved that participants were able to stretch their finances better after participation in the cooking demonstrations and nutrition education sessions, a valuable factor given the limited financial resources.

Power is also a huge challenge in Nigeria, so I made sure we had a stand-by generator set in case of power outage. Timing is another big problem in Lagos, Nigeria. Therefore, I prepared some of the foods, such as boiled root vegetables millet and other grains ahead of time and used PowerPoint presentations to demonstrate what I had done in their absence.

Another barrier I discovered was the unjustified conviction that one knows a lot about nutrition. On top of that, participants showed a lack of improvisational skills while using cooking apparatus. An example is that of the oven. I taught the participating women a simple technique of placing clean sand at the bottom of a big pot. Subsequently, by placing a smaller pot or baking pan inside the bigger one, which rests on stilts to avoid direct heat, one creates an oven that can be used to

bake anything, especially in a peculiar environment like Nigeria. Hence, by offering Nigerian women simple techniques that enrich their ability to prepare proper meals, I empowered them to bring about behavioral change and work towards a healthier lifestyle. In conclusion, after participating in the nutrition education classes, Nigerian women were familiar with the ingredients used and capable of preparing them by applying new techniques. The outcome of the project indicated that with hands-on cooking demonstrations and nutritional education, the conditions required to facilitate behavioral change, can be created quickly.

Future Projects. As a result of the project’s effectiveness, I will continue to offer cooking demonstrations and nutrition education in Ikeja, Lagos, Nigeria. Moreover, I aim to introduce them in other parts of the state and Nigeria. Furthermore, the program will be broadcasted on television to reach a wider audience. On top of that, I plan to host food fairs to showcase nutrient dense, seasonal, healthy, local foods. While doing so, I hope to reintroduce vegetables, local seeds and grains and to provide nutritious food in supermarkets and markets. These food fairs can make a difference in simplifying nutrition education.

Recommendation For Action. I would advise other initiators to focus more on giving people an understanding of ‘why’ foods are either nourishing or depleting. When there is a basic understanding, making the right choices will not be difficult. Moreover, I recommend other initiators to focus on overcoming the aforementioned barriers that might limit the effectiveness of educational efforts, such as limited resources, power and timing difficulties, as well as a lack of improvisational skills. Besides that, educational initiatives can only be sustained in a peculiar country like Nigeria when such programs are constantly in people’s faces, i.e. on television, healthy cooking competitions/fairs and in the social media.

References

- CIA The World Factbook. https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/fields/2052.html Accessed November 24, 2014.

- NPC (2001). http://nascp.gov.ng/demo/wp-content/uploads/2014/02/NATIONAL-POLICY-ON-FOOD-AND-NUTRITION-IN-NIGERIA-2001-NPC.pdf

- FAO (2004). Incorporating Nutrition Considerations into Development Policies and Programs. Brief for Policy-makers and Program Planners. The Role of Nutrition in Social and Economic Development. Overview of nutrition in human resource and economic development http://www.fao.org/docrep/007/y5343e/y5343e00.htm

- Sustainable Diets and Biodiversity. Directions and solutions for policy, research and action., November 3. http://www.fao.org/docrep/016/i3022e/i3022e.pdf

- Odum F. Tackling malnutrition with high-energy foods tops agenda. THE GUARDIAN. May 9, 2014: 4.

- Ogundipe S. Nigeria must invest in children’s nutrition. Nigeria World News. February 21, 2012. Retrieved from http://www.nigeria-news-world.com/2012/02/nigeria-must-invest-in-childrens.html

- National Demographic and Health Survey 2013.

Children’s Nutritional Status http://dhsprogram.com/pubs/pdf/SR213/SR213.pdf

Retrieved 20 Nov 2014 - Gray VB, Byrd SH, Cossman JS, Chromiak JA, Cheek W, Jackson G. Parental attitudes toward child nutrition and weight have a limited relationship with child’s weight status. Nutrition Research. 2007; 27: 548-558.

- Taire M, Ajumobi F. (2013). Nigeria: Education on Good Food Choice- Solution To Child Nutrition Challenges. http://allafrica.com/stories/201304120463.html

Accessed Nov 24 2014. - Perez RC, Aranceta J. School-based nutrition education: lessons learned and new perspectives. Public Health Nutr. 2001; 4(1A): 131-139.

- Judd, J, Frankish CJ, Moulton G. Setting standards in the evaluation of community-based health promotion programs— a unifying approach. Health Promot Int. 2001; 16(4): 367-380.

- FAO. The Need for Professional Training in Nutrition Education and Communication. http://www.fao.org/ag/humannutrition/29493-0f8152ac32d767bd34653bf0f3c4eb50b.pdf Published June 2011. Accessed Dec 8, 2014

Table 1. Project outline

Table 2. Food Products Used in the Project

- CIA The World Factbook. https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/fields/2052.html Accessed November 24, 2014.

- NPC (2001). http://nascp.gov.ng/demo/wp-content/uploads/2014/02/NATIONAL-POLICY-ON-FOOD-AND-NUTRITION-IN-NIGERIA-2001-NPC.pdf

- FAO (2004). Incorporating Nutrition Considerations into Development Policies and Programs. Brief for Policy-makers and Program Planners. The Role of Nutrition in Social and Economic Development. Overview of nutrition in human resource and economic development http://www.fao.org/docrep/007/y5343e/y5343e00.htm

- Sustainable Diets and Biodiversity. Directions and solutions for policy, research and action., November 3. http://www.fao.org/docrep/016/i3022e/i3022e.pdf

- Odum F. Tackling malnutrition with high-energy foods tops agenda. THE GUARDIAN. May 9, 2014: 4.

- Ogundipe S. Nigeria must invest in children’s nutrition. Nigeria World News. February 21, 2012. Retrieved from http://www.nigeria-news-world.com/2012/02/nigeria-must-invest-in-childrens.html

- National Demographic and Health Survey 2013.

Children’s Nutritional Status http://dhsprogram.com/pubs/pdf/SR213/SR213.pdf

Retrieved 20 Nov 2014 - Gray VB, Byrd SH, Cossman JS, Chromiak JA, Cheek W, Jackson G. Parental attitudes toward child nutrition and weight have a limited relationship with child’s weight status. Nutrition Research. 2007; 27: 548-558.

- Taire M, Ajumobi F. (2013). Nigeria: Education on Good Food Choice- Solution To Child Nutrition Challenges. http://allafrica.com/stories/201304120463.html

Accessed Nov 24 2014. - Perez RC, Aranceta J. School-based nutrition education: lessons learned and new perspectives. Public Health Nutr. 2001; 4(1A): 131-139.

- Judd, J, Frankish CJ, Moulton G. Setting standards in the evaluation of community-based health promotion programs— a unifying approach. Health Promot Int. 2001; 16(4): 367-380.

- FAO. The Need for Professional Training in Nutrition Education and Communication. http://www.fao.org/ag/humannutrition/29493-0f8152ac32d767bd34653bf0f3c4eb50b.pdf Published June 2011. Accessed Dec 8, 2014